Nuclear risks in the Russian Arctic during the war in Ukraine

The following speech was given by Bellona nuclear expert Dmitry Gorchakov at the Arctic Frontiers conference, which was in session in Tromsø, Norway

News

Publish date: 04/11/2025

Written by: Aleksander Nikitin

Translated by: Charles Digges

News

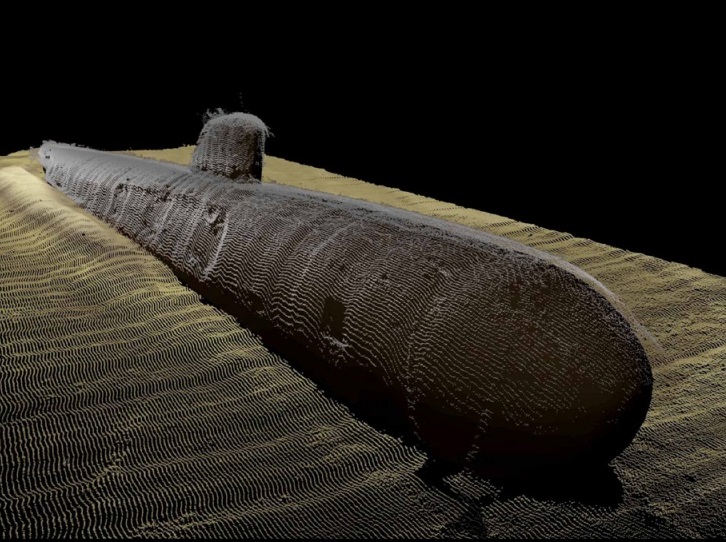

Recent reports in Russian media claiming that the government has allocated funds in the 2026–2028 federal budget for raising two sunken nuclear submarines — K-27 and K-159 — from Arctic waters have sparked widespread interest among experts and the public, both in Russia and abroad.

The main question is: why now? Why has Moscow suddenly revisited these long-forgotten wrecks and decided to fund their recovery projects amid one of the most challenging periods in the country’s recent history?

Before drawing any conclusions, it’s worth noting that the reports about new budget allocations for the submarines all cite Rosatom, the state nuclear corporation. Yet a review of Rosatom’s official news outlets — rosatom.ru and atomic-energy.ru — reveals no such announcement.

That absence is puzzling. The start of such a high-profile project as raising sunken nuclear submarines could hardly have gone unnoticed by Rosatom’s own information channels. Moreover, none of the corporation’s executives have commented publicly on this supposed budget decision or on any line items related to it.

This has led many analysts — including those close to Rosatom — to suspect that journalists may have misunderstood what is actually being financed. Most likely, the allocations concern broader efforts to eliminate Russia’s “nuclear legacy” — the remnants of Cold War–era nuclear and naval infrastructure scattered across the Arctic and Far East, which include these submerged submarines.

Rosatom chief Alexey Likhachev has repeatedly declared his intention to clean up the Arctic’s radioactive legacy. He has done so, notably, after meetings of the Maritime Board of the Russian Federation, which is chaired by Nikolai Patrushev, a close ally of President Vladimir Putin.

Putin himself reinforced this priority in February 2023, when he amended Russia’s Strategy for the Development of the Arctic Zone and National Security until 2035. That decree set a deadline of 2031 to 2035 for completing the rehabilitation of territories contaminated or affected by sunken nuclear and radioactive objects.

Rosatom submitted a budget request for this work to the Ministry of Finance at the end of 2023. The proposal was supposed to be reviewed in 2024 but now appears to have been postponed to 2025 — which aligns with the current discussions about new funding.

Adding intrigue, just before the budget was approved, the Kurchatov Institute — headed by Mikhail Kovalchuk — announced an unexpected initiative: by the end of 2025, it plans to complete a prototype of an experimental underwater monitoring station designed to track radiation levels near the site of the sunken K-27 submarine.

It’s unclear what role this project might play if K-27 is ever raised, but it’s reasonable to assume that the Kurchatov Institute, along with Rosatom and the Maritime Board, may have lobbied for budget allocations by highlighting their projects’ alignment with Putin’s 2023 Arctic directive.

These agencies are all eager to emphasize their relevance in the strategic development of the Arctic region and the Northern Sea Route, which has become a major geopolitical and economic focus for the Kremlin.

Discussions about raising sunken nuclear submarines first gained momentum after the Kursk tragedy in 2000, which exposed the Russian Navy’s lack of equipment not only for salvage operations but even for providing basic emergency assistance to stricken vessels.

For nearly two decades, there was no sign that Russian shipyards or research institutes were developing technology for such complex recovery missions. Only in 2019, at the Neva-2019 exhibition, was a model unveiled for a specialized vessel to work with sunken objects — a project estimated at around 10 billion rubles (or $123 million in 2019 prices).

The ship was supposed to be built in St. Petersburg or Severodvinsk, but no progress has been reported since. In recent years, both shipbuilding centers have been fully occupied with constructing nuclear submarines for the Navy and icebreakers for the Northern Sea Route, leaving little room for auxiliary projects.

When it comes to the actual feasibility and environmental risks of raising these submarines, the environmental organization Bellona has extensively analyzed the issue in its report “Nuclear Legacy in the Russian Arctic and Prospects for Its Elimination (Status as of the End of 2023).” In it, we note that Russia currently lacks the technical means and infrastructure to carry out such complex operations.

Given the country’s current economic strain, the ongoing war, and the crisis in its design bureaus and shipbuilding industry, the prospect of Russia actually raising the K-27 or K-159 submarines in the foreseeable future seems highly improbable.

The following speech was given by Bellona nuclear expert Dmitry Gorchakov at the Arctic Frontiers conference, which was in session in Tromsø, Norway

Russia has officially withdrawn from an international environmental agreement that brought to bear billions of dollars from EU nations and the United States on addressing the nuclear legacy of the Soviet Union.

This op-ed piece, written by Bellona.org editor Charles Digges, originally appeared in The Moscow Times. The Russian Arctic stands to remain one ...

Bellona publishes the new report on the environmental consequences of the Northern Sea Route