Nuclear risks in the Russian Arctic during the war in Ukraine

The following speech was given by Bellona nuclear expert Dmitry Gorchakov at the Arctic Frontiers conference, which was in session in Tromsø, Norway

News

Publish date: 13/02/2025

News

The so-called Multilateral Nuclear Environmental Program in the Russian Federation (MNEPR) had since 2003 brought together financial and technical resources from some of Europe’s biggest economies, as well as institutions like the European Commission, to launch massive efforts to clean up decommissioned Soviet nuclear submarines and the irradiated bases in the Arctic that served them.

It had also broadly functioned as an instrument of hope by providing an arena where Russia and the West could come together and work to improve the environment for people on both sides of what used to be the Iron Curtain. The cooperative agreement had endured some of the most trying political disputes of the early 21st century, such as Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Even Russia’s invasion of Ukraine hadn’t officially killed it. But in a terse announcement late last year, Russian officials reported they had prepared a “denunciation” of the MNEPR, which facilitates Moscow’s withdrawal from the agreement—a legal necessity under Russian law given that the agreement was ratified by Russia’s parliament.

Earlier this year, Bellona’s Aleksander Nikitin—who was instrumental in helping Europe and Russia direct much of the agreement’s funding—sat down with journalist Vladislav Gorin, who runs the What Happened podcast for Meduza, the independent Russian newspaper now published in exile from Riga, Latvia, to discuss what this agreement accomplished, and what it’s unraveling will mean. We’re grateful to Meduza for allowing us to publish this edited and translated transcript of their interview.

Vladislav Gorin – Which agreement is Russia withdrawing from now?

Aleksander Nikitin – This is the so-called Multilateral Nuclear Environmental Program, adopted and ratified by Russia in 2003. It is unfortunate that the country is leaving the program so easily now because we know how important it was for environmental protection efforts. In addition to this program, there were many other significant programs at the time of its development and ratification, which funded various projects aimed at eliminating the so-called nuclear legacy of the Soviet Union.

– What has been accomplished since the program was enacted in 2003?

The first program that was adopted was the so-called Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) Program, also known as the Nunn–Lugar Program, initiated by U.S. Senators Sam Nunn and Richard Lugar. This was a massive program that began after the collapse of the Soviet Union and lasted until about 2010. It focused on eliminating excess nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons, as well as their delivery systems.

At the same time, there was another program known as the HEU-LEU Agreement or the “Megatons to Megawatts” program. This was negotiated between the U.S. and Russia in the late 1990s. Under this agreement, approximately 500 tons of highly enriched uranium (HEU) were to be converted into low-enriched uranium (LEU) and used in nuclear power plants. The process was expected to take around twenty years—since it was signed in 1995, it was set to run until 2015.

Additionally, the G8 agreed on the so-called Global Partnership. In 2002, at the Kananaskis Summit in Canada, the G8 signed this agreement, often referred to as “10 plus 10 over 10.” Under this agreement, Russia received $20 billion—$10 billion contributed by the G8 countries and another $10 billion from the United States. In total, $20 billion was allocated over ten years to dismantle excess nuclear weapons and their delivery systems.

Why am I listing all of this? Because MNEPR, the agreement we are discussing today, was a crucial framework that encompassed all these programs. It allowed for the coordination of essential bureaucratic matters, such as tax procedures, nuclear safety regulations, and legal responsibilities, ensuring the effective execution of these programs and projects.

This was vital because bureaucracy functioned according to its own rigid rules on both sides. Without coordinating the procedures outlined in the Multilateral Nuclear Environmental Program, it was often impossible to utilize the allocated funds. For instance, $20 billion was secured under one program, $10 billion under the CTR program, and about $10 billion under the HEU-LEU program. These were enormous sums contributed by multiple countries, but their use was frequently hindered by the lack of agreed-upon procedures.

Another initiative was the “Northern Dimension Environmental Partnership”, which included a project called “The Nuclear Window.” This project specifically dealt with nuclear waste management, in addition to general environmental initiatives addressing water and conventional waste. The Nuclear Window focused on dismantling nuclear submarines, handling spent nuclear fuel, and managing radioactive waste storage sites in northern and eastern Russia. Contributions to this project came from Northern European countries and the European Commission, while the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development managed financial transactions.

However, for all these programs and projects to function, the MNEPR agreement was necessary. I haven’t even mentioned other agreements between, for example, the U.S. Department of Defense and the Russian Ministry of Defense. The funds gathered through these initiatives had to be used according to the regulations of both donor countries and Russia. That’s why MNEPR was essential, and why it was eagerly awaited. Bellona, where I was already working at the time, closely monitored these agreements and helped initiate these programs, as environmentalists were deeply concerned about eliminating Russia’s nuclear legacy in the north.

MNEPR was adopted and ratified in Russia in 2003 and remained in effect. Some Russian media claim that it ended around 2017. However, the reality is different—it wasn’t just about funding running out (although some projects did face financial constraints as some countries left while others remained involved until 2022, when the war began). The real significance of MNEPR was in regulating procedural matters. That is what we now regret—the fact that Russia’s withdrawal has ended this regulatory framework.

-Why is Russia withdrawing? What does the explanatory note say? Should we blame Russia for this decision, considering the war and sanctions? Funding from Western countries for anything related to Russia would likely have been problematic anyway. Wouldn’t these projects have stopped regardless?

Some projects have indeed stopped, but others might have resumed in the future. The legacy we are dealing with still requires attention. For instance, there are still sites in northern Russia that need financial investments to complete cleanup operations.

For example, in Andreyev Bay, some spent nuclear fuel remains in an emergency storage facility, a well-known issue we have reported on extensively. We continue to monitor this site daily. Similarly, the Gremikha submarine base remains in limbo because several nuclear-hazardous facilities there have yet to be fully decommissioned and made safe.

However, our greatest concern is the sunken and submerged nuclear and radiological hazards.

Recently, we published a review examining the state of these hazardous objects before the war and predicting their future under the current circumstances—given the war, sanctions, and the withdrawal of international participants, leaving Russia to deal with them alone. According to our data, at least six sunken nuclear-hazardous objects remain—primarily nuclear submarine reactors still containing spent nuclear fuel. Ideally, these should be recovered.

Beyond that, there are 17,000 containers and various small vessels containing radioactive waste, which have been officially recorded as sunk. These must also be monitored. While they may not pose an immediate threat like spent nuclear fuel still inside reactors, ongoing observation and decision-making are necessary.

The Arctic and Northern Seas, where these objects are submerged, will always be of critical importance—regardless of the war, political situations, or any other circumstances. The Arctic will remain the Arctic.

-Let’s discuss the 2011 report “Problems of Radiation Remediation in Arctic Seas: Solutions and Approaches.”Here’s an excerpt detailing what nuclear waste remains in Russia’s northern seas—left primarily from the Soviet Union—and the environmental burden inherited from that era:

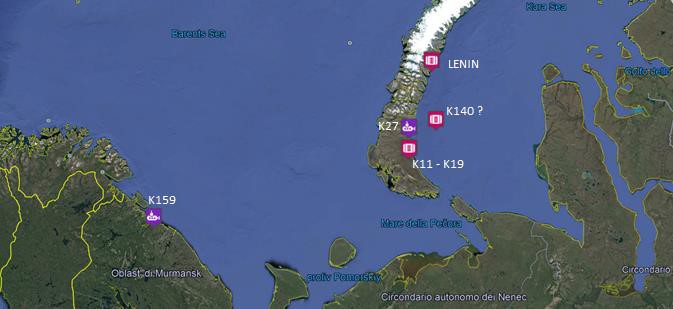

“Currently, around 18,000 objects of varying degrees of radiation hazard lie on the seabed of the northwestern Arctic. Most of these were dumped during the Cold War and contain radioactive waste (RAW) from the operation of nuclear submarines of the Northern and icebreaker fleets. Seven of these radioactive legacy objects contain fissile materials, specifically spent nuclear fuel based on enriched uranium, and are classified as nuclear-hazardous. The most notable among them are three nuclear submarines: one of them, K-27, which had two nuclear liquid-metal reactors, was deliberately sunk in 1981 in Stepovoy Bay off the eastern coast of Novaya Zemlya. The other two submarines sank accidentally: K-278, known as the Komsomolets” in 1989 in the Norwegian Sea, and K-159 in 2003 in the Barents Sea.

Additionally, in the 1960s, five reactor compartments with shipborne and marine nuclear power plants were dumped in bays off the eastern coast of Novaya Zemlya. Two of these compartments contain spent nuclear fuel (SNF), as does a special container holding a shielding assembly with SNF elements from one of the reactors of the nuclear icebreaker “Lenin”. In the Novaya Zemlya depression of the Kara Sea, a barge was sunk containing an emergency reactor with SNF that had been removed from a nuclear submarine, designated Order No. 421.”

A vast amount of radioactive waste was either deliberately dumped or lost in accidents. What should we understand about this unpleasant legacy of the Soviet Union? Some reports suggest that, for example, radiation levels in the Black Sea or the Mediterranean are actually higher than in the Arctic. They argue that these reactors were designed with protective mechanisms, which are still functioning. They might remain intact for decades, or they may be undergoing erosion. How significant is the danger—both in terms of severity and scale?

– At the end of 2023, we conducted a brief review to summarize what is currently lying on the Arctic seabed and how dangerous it is. The information you mentioned is largely correct. I would even add that at one time, we conducted an extensive study of what was dumped, how much was dumped, and in which seas and trenches.

To gather information, we met with people—many of whom are no longer alive—who were responsible for these dumpings. These were the officials who made the decisions. However, when we tried to get precise answers on the locations and quantities of dumped materials, many of them simply could not provide clear information. They told us that in some cases, the dumping was chaotic and unplanned.

For example, a barge carrying radioactive waste would be sent out to sea with orders to dump the waste at specific coordinates. But for various reasons—bad weather, technical issues, or simply arbitrary decisions by the crew—the waste was often dumped elsewhere.

Today, researchers investigating the Arctic seabed, particularly around Novaya Zemlya in the Kara Sea, often find that nothing is located at the official coordinates. As a result, we have only an approximate understanding of where the waste is. We have fairly good knowledge about the locations of large objects, particularly those containing spent nuclear fuel. But for smaller objects, we can only make rough estimates.

–Which objects pose the greatest threat?

When I chaired the Environmental Commission of the Public Council of the Rosatom State Corporation, experts worked on identifying which objects should be raised first based on their level of danger.

Experts unanimously agreed, and still insist, that the K-27 submarine must be raised first. The issue is not only the liquid-metal coolant used in its reactors but also the highly enriched nuclear fuel inside them. Unlike typical nuclear submarine reactors, which use thermal neutrons, K-27 had an intermediate neutron reactor requiring highly enriched fuel.

Because of this, scientists, engineers, and nuclear specialists believe that K-27 should be the first to be raised—especially since it lies at a relatively shallow depth of around 40 meters.

For comparison, the K-140 is at a depth of 300 meters, the Komsomolets is at a depth of 1,000 meters.

There is no discussion about raising Komsomolets—it lies far too deep, and no country currently has the technology or resources to carry out such an operation. However, it is constantly monitored, as it not only has a nuclear reactor but also torpedoes with nuclear warheads. Monitoring missions are periodically conducted to assess radiation levels.

As for K-27, raising it would not be very difficult. In Gremikha, with the help of France, a unique facility was built specifically for unloading spent nuclear fuel from submarines with liquid-metal reactors. Handling SNF from such reactors requires specialized technology and equipment—something that only exists at this facility in Gremikha.

All other Soviet/Russian submarines that used liquid-metal reactors have had their fuel safely removed and transported to proper disposal sites. K-27 is the last one remaining. The Gremikha facility, built with French funding, was maintained for precisely this purpose.

Another submarine that must be raised is K-159, which sank in 2003.

-Why does K-159 worry environmentalists?

– Unlike the other reactor compartments deliberately dumped around Novaya Zemlya (except K-27), those other compartments were at least properly prepared for long-term underwater storage. Special preparations were made to ensure that their reactors could remain submerged indefinitely with minimal leakage risk. However, K-159 sank accidentally while being towed for disposal and SNF removal.

It sank in a highly problematic location—near the entrance to the Kola Bay, an area with heavy civilian and fishing activity. This is a key fishing region where commercial vessels operate.

K-159 lies at a depth of 170 meters, and its reactors were not sealed for long-term underwater storage. Over time, the SNF inside its reactors will begin to leak, contaminating the surrounding waters.

– What needs to be done?

– The K-27 must be raised first because it contains highly enriched nuclear fuel. It lies at a manageable depth of 40 meters and the necessary technology for its safe dismantling already exists at Gremikha. K-159 must also be raised because it sank accidentally, without proper reactor sealing. It also lies near the entrance to the Kola Bay, in a critical fishing zone. If left in place, radioactive leakage will occur over time.

Before the war, these concerns were being discussed with international partners, particularly within the framework of the “Nuclear Window” initiative I mentioned earlier. MNEPR, which is now closed, would have played a role in these efforts. Now, however, Russia has been left alone to deal with these hazardous legacy sites. That is the current situation.

As for the other objects, they need to be monitored, and expeditions must be regularly sent to observe and track them—especially those containing spent nuclear fuel—to prevent leaks, contamination, and other hazards. This is a long and very meticulous process, but it must be carried out. This is the situation with the sunken and submerged objects.

– I’d like to talk about another category of objects—lighthouses located along the Northern Sea Route that operate on radioisotope thermoelectric generators. Essentially, these are nuclear-powered lighthouses installed during Soviet times. They emit both a radio signal and a light beacon without requiring human presence. As I understand it, Rosatom is currently overseeing them. There have been some threats associated with them. In the mid-2000s, near Norilsk, one of these facilities was looted, and people searching for scrap metal literally discarded radioactive material after dismantling it. Could you talk about these lighthouses and such exotic threats from radioactive objects?

– Yes, this was another issue, related to the elimination of this legacy. However, unlike the sunken submarines, this was a civilian rather than military legacy. According to our information, all lighthouses with radiation sources have now been decommissioned. Norway primarily funded this process, while Japan and the U.S. contributed in the eastern regions.

A few of these lighthouses remained, and yes, there were cases where local scavengers found and tampered with them, leading to incidents like the one you mentioned. But as of now, these lighthouses no longer exist, so we consider this problem resolved and have written about it.

– To summarize, what can be said about the dangers if these objects are not dealt with? Over what time frame could they become a serious problem?

– According to our assessments and those of the designers of the K-27 submarine, they say that if we don’t raise K-27 within the next five years, we may have to reconsider and perhaps leave it untouched altogether. Why? Because it has been lying there since 1981, meaning 45 years have already passed.

The reactor compartment and its structural casing may lose integrity and begin to deteriorate. While a nuclear reactor is designed as a sealed pressure vessel, it still has various inlets and outlets for operational purposes.

Over 40-50 years, everything inevitably corrodes and weakens. The structure is deteriorating due to exposure to seawater. On the other hand, the radioactivity of the fuel is also decreasing over time, making it less hazardous—this is simply the physics of nuclear fuel, which undergoes decay after the nuclear reaction ceases.

Some experts have expressed concerns about the potential for a spontaneous chain reaction—essentially, a small nuclear explosion. They base this on the fact that the reactor fuel in K-27 is highly enriched.

It is difficult to say what exactly will happen, when it will happen, or how it will happen. However, those who argue that the next five years are critical still advocate for raising K-27 as soon as possible.

K-159, on the other hand, is more dangerous because fuel leakage will begin much sooner. As I mentioned, it was never prepared for long-term underwater storage. The reactors were not sealed, the submarine was not decontaminated, and no protective measures were taken.

Once fuel leakage begins, we will need to assess: The rate and intensity of the leakage, how long the leakage will continue, where the contamination will spread and how ocean currents will carry the radioactive material. This means that constant monitoring around K-159 is absolutely necessary.

Objects lying at a depth of 170 meters are, on the one hand, not extremely deep. However, on the other hand, we saw how difficult it was to raise the Kursk submarine. Russia did not have the resources to raise the Kursk alone and had to seek help from foreign partners.

So, how do they plan to raise K-159? I don’t know. To do this, they first need to develop all the necessary lifting equipment, which, unfortunately, does not yet exist. Perhaps they are working on it—perhaps not. Everything is quite secretive at the moment.

– That’s what I wanted to ask. Why the pessimism? Couldn’t the Russian Federation fund and carry out these operations on its own? Why is international cooperation necessary?

– Yes, of course, many people have argued that Russia should develop its own capabilities. Since the late 1990s, we have been saying that funding should not only be used for cleaning up contaminated sites but also for developing domestic technologies.

However, let’s take the Kursk disaster as an example. The Kursk sank in just 100 meters of water. That is nothing for a submarine of its size—it was nearly 100 meters long itself. I have spent a large part of my life serving on submarines. I know what 100 meters of water means for a submarine—it is nothing. And yet, Russia could not lift the Kursk alone. This was recent history.

Since then, we have not seen or heard of any significant developments in recovery technology. Maybe they exist. Maybe we just don’t know about them. But I highly doubt that Russia is prepared to lift K-159.

Meanwhile, Russia claims to be a great naval power. Recently, there was talk of developing a submarine tanker to transport liquefied natural gas. Some academician even announced plans to build an underwater gas carrier.However, there are no shipyards capable of building such vessels—they simply do not exist.

Currently, they are slightly deepening the Severodvinsk shipyard to accommodate the repair of modern submarines. The shipyard basin is being dredged, and everyone understands what needs to be done. But it hasn’t been completed yet. Maybe it will be.

Maybe new facilities will be built in the Russian Far East, where they are reconstructing the Zvezda shipyard. But for now, these capabilities do not exist. If they do develop them, great—then Russia can handle it alone.

– Would it be fair to say that international cooperation was important from a management perspective? It provided mutual oversight and accountability, making it harder to cut corners.

– Yes, absolutely. International involvement provided oversight. This is why we fought so hard to keep Norway involved in these projects until the very end. And it wasn’t just about Norwegian funding—it was about transparency and accountability.

For example, Andreeva Bay, where spent nuclear fuel (SNF) from Soviet submarines was stored, was an infamous environmental disaster zone. Handling SNF removal from crumbling Soviet-era storage facilities required constant vigilance.

I won’t call it control, because that’s too strong a word. But at least we needed to know what was happening—how the money was being spent, whether technologies were actually being used, and whether anything was getting done at all.

Because let’s be honest—in Russia, money can appear, and just as easily, it can disappear without a trace. That’s why international oversight was crucial—especially for public trust, both in Russia and abroad. People had a right to know how serious the risks were and whether taxpayer money was being used effectively to mitigate them.

– In your opinion, how much sense is there in terminating this cooperation, since we want to continue doing various things related to radioactive materials without any control? Can we recall 2019 – the accident with the Losharik deep-sea vehicle. Is this a factor or are these unrelated things? And does the process of neutralizing old radioactive waste not interfere with the production, testing, and dumping of new radioactive waste?

– I was a little surprised when I heard about the MNEPR being denounced, I was surprised that Russia agreed to close this program, because, strictly speaking, this program could remain for a long time, in case, let’s say, something changes. Well, I still believe that maybe in 10-15 years, maybe in 20, there will be changes, when this cooperation can once again be established. And this cooperation should be again; it is impossible to live behind the Iron Curtain.

What if, then, some projects are needed that need to be implemented, similar to those that were implemented earlier, and this program, it will already be ready. Because I remember how hard it was to get it going in the first place. Before this program was adopted, a lot of money was just lying around. It could not be used because there were no conditions and rules that I spoke about, these procedures were not agreed upon— judicial, tax, nuclear liability, and so on. This is very important.

This program, in fact, is about this, about these procedures mainly. And let it lie there, this already an agreed upon program, let these agreed upon procedures lie there and exist. This does not say anything about access to secret facilities. If, for example, you do not want to let someone in somewhere or share something, for example, your Losharik sank, well, it sank, just do not talk about it and especially do not let anyone in to have a look. There, in such questions about Losharik this program does not work, there is no international money there, so who did it bother? But they decided what they decided.

The following speech was given by Bellona nuclear expert Dmitry Gorchakov at the Arctic Frontiers conference, which was in session in Tromsø, Norway

"Maritime transport along the Northern Sea Route remains a bad idea. Even with a warmer climate, cold, wind and darkness will define the Arctic winter," said Bellona's Senior Adviser Sigurd Enge to a packed hall at the Arctic Frontiers conference.

At the beginning of the year, reports in the German and Russian press suggested an approximate 70% increase in uranium imports from Russia to Germany in 2024. But does this reflect broader European trends? It does not.

This op-ed piece, written by Bellona.org editor Charles Digges, originally appeared in The Moscow Times. The Russian Arctic stands to remain one ...